Maternal Ecologies

SPECIAL EDITION | The ecological illuminations of Anne Berg | Cradle: New fiction | Spotlight on Hannah Rowan

I was inspired to put together this special extra edition of Art & Ecology to share some of the ideas around maternal ecology I’ve begun to explore through curating the group show Cradle at 28 Shacklewell Lane, E8, London.

“Drawing on Sophie Strand’s assertion that everyone is simultaneously both a mother and mothered, Cradle further considers motherhood as a route for engaging with the multivalence of existence within an environment. Strand writes, “Your body mothers you. And child-like you nuzzle deep inside other bodies. Forest bodies. Spore bodies… Everybody is a mother. Everybody can turn to the other and offer a song, a wink, a fierce embrace.” In this formulation, experiences of gestation, birth, and care might offer a sharpening lens for adopting radical forms of labour and care outside the family unit. Cradle attempts to centre the maternal gaze as a method of re-examining the self as something leaky and unbounded, vibrantly emerging within the complex interconnected webs of our ecosystems.”

Cradle

Written on the train on the way to the opening of Cradle

A mice! A mice! A mice! You shout at me, pulling a toy from a pile.

Apple, banana, bowl, purple, help, Mummy! Help, Mummy! Cuddle, Mummy! No! Down, down!

Row, row, row, your boat gently down the stream…

Changing your clothes, you struggle and twist your little body under my hands, or you lie still and smile and clap. You point beneath you – mat! – then show me your toes. You laugh when I pretend to eat your feet and I never want this moment to end.

Later, you scratch my face with your nails, which I never keep short enough because we both hate the process of cutting them. The only way to keep you calm under the clippers is to show you pictures of yourself in the bath, hair slicked back, you and not-you. You look so happy in these pictures, splashing, that I want to show them to everyone I meet, but I don’t because I theoretically believe in your right to privacy and I don’t want you to hate me when we’re both older.

You are playing an invisible game involving plastic animals. When I interrupt, you stare at me blankly, like the London foxes I used to come across on my way back from drinking wine with a friend, walking fast, arms crossed. Glossily orange, globe-eyed, feral as ghosts, pausing under street lights before trotting back into the darkness, held by the night.

There are no foxes now in this place of hedgerows and overgrown bus stops and thickly reeded streams. We left them behind with the city.

You have seen them in books, but you don’t yet know the wildness of their smell, the urban abrasiveness of their screeching.

You’re bright-eyed with tiredness and bedtime can’t come soon enough now. I have been reading an article on my phone about rising sea temperatures and you’re angry that I’m not paying you attention. You pull all the books from your shelves then cry when one falls on your foot.

Mummy, Mummy, cat, cat, CAT!

I put my phone away and hand you your toy cat. I feel guilty, more so than usual. You refuse a cuddle.

…if you see a crocodile, don’t forget to scream!

We sit down to read a book. Poor old fox has lost his socks. What are we set to lose?

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream!

There is a quiet scuffling from the roof. I stare at the ceiling as though I can see through it and think about all the creatures that shared our home before we numbered ourselves as a family of three.

Mice in the attic, then rats, mercifully briefly. Ants that marched purposefully under the front door. Woodlice, crunching under my slippers when I go into the kitchen to make breakfast. There are moths in the wardrobes and a pair of swifts nested under the eaves one year, but they didn’t come back again.

Before I place you in your bed, you touch my face in a way that seems intended to be gentle, but isn’t. Eyes, you say, Mummy, eyes.

Yes, eyes. Where are your eyes?

Eyes! Nose! Ears! Pressing your hands to your face, smiling then suddenly serious. You make a kissing noise and press your forehead to my mouth.

You are eighteen months old and a small part of me wishes you will never learn any more words, that you will never grow, that you will never lose your delight in being able to name my facial features and identify them as mine.

Eyes, Mummy, Eyes!

I kiss your neck and you laugh, pushing me away. When I stop, you are stern. More! More!

When I was younger, I thought that survival of the fittest meant that the strongest and fastest would survive, would pass their genes onto the next generation, beating off the competition in the evolutionary race.

Now I see that Darwin meant that the survivors will be those best adapted to their environment; the best fit with their surroundings. Those who collaborate with the species and places around them, brilliantly varied threads in the same tapestry.

I was once your only environment, your tiny body fitted inside mine like a ripening seed.

Even after you were born in a shuddering rush of fluids, it took you months to learn that we are not the same person. Even now you cry when I leave a room, wrenching part of me back to you.

How are we fitted to our environment?

You are growing into a world that is changing faster than I can fathom and grasslands are burning and forests are falling and tides are rising and I feel it in my body, our body, the body that contains, holds, cradles you, past, present, and unknowable future.

Row, row, row your boat gentle down the river…

Your rowing is not gentle, you fling yourself back and forth with abandon, fully trusting that I won’t let your hands slip from mine.

If you see a polar bear, don’t forget to shiver!

Anne Berg’s ecological illuminations

In 1971, Anne Berg and Monica Sjöö co-authored a manifesto for a pamphlet titled “Towards a Revolutionary Feminist Art”. Their claims are bold, unequivocal, and unapologetic:

“WE SAY NO TO EMPTY ABSTRACTIONS, to the ‘art for art’s sake’ philosophy of the privileged white middle-class male art world. We THE OPPRESSED cannot afford this empty play with words and forms, for us the important task is to convey to people to WOMEN their dignity and strength and beauty – OUR PAST AND FUTURE.”

Their urgency is made clear by their use of capitalisation, exclamation marks, and hurried grammar. They argue for art that reflects reality as experienced by women, depicting not only everyday occurrences of being a mother, daughter, or underpaid worker carrying out gendered labour, but also the realities of the female body-soul relation, repressed knowledge traditions, and a worldview that rejects the supremacy of patriarchal capitalism.

For Sjöö and Berg, this meant portraying ancient goddesses, childbirth, medusas, and scenes of contemporary life rich with Celtic symbology. Berg had studied fine art at the University of Newcastle from 1960 to 1963 under Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton. As well as giving birth to her first child during her studies, she also rejected her teachers’ insistence on the primacy of abstraction, instead creating work about motherhood at a time when this was seen as an inappropriate subject for art.

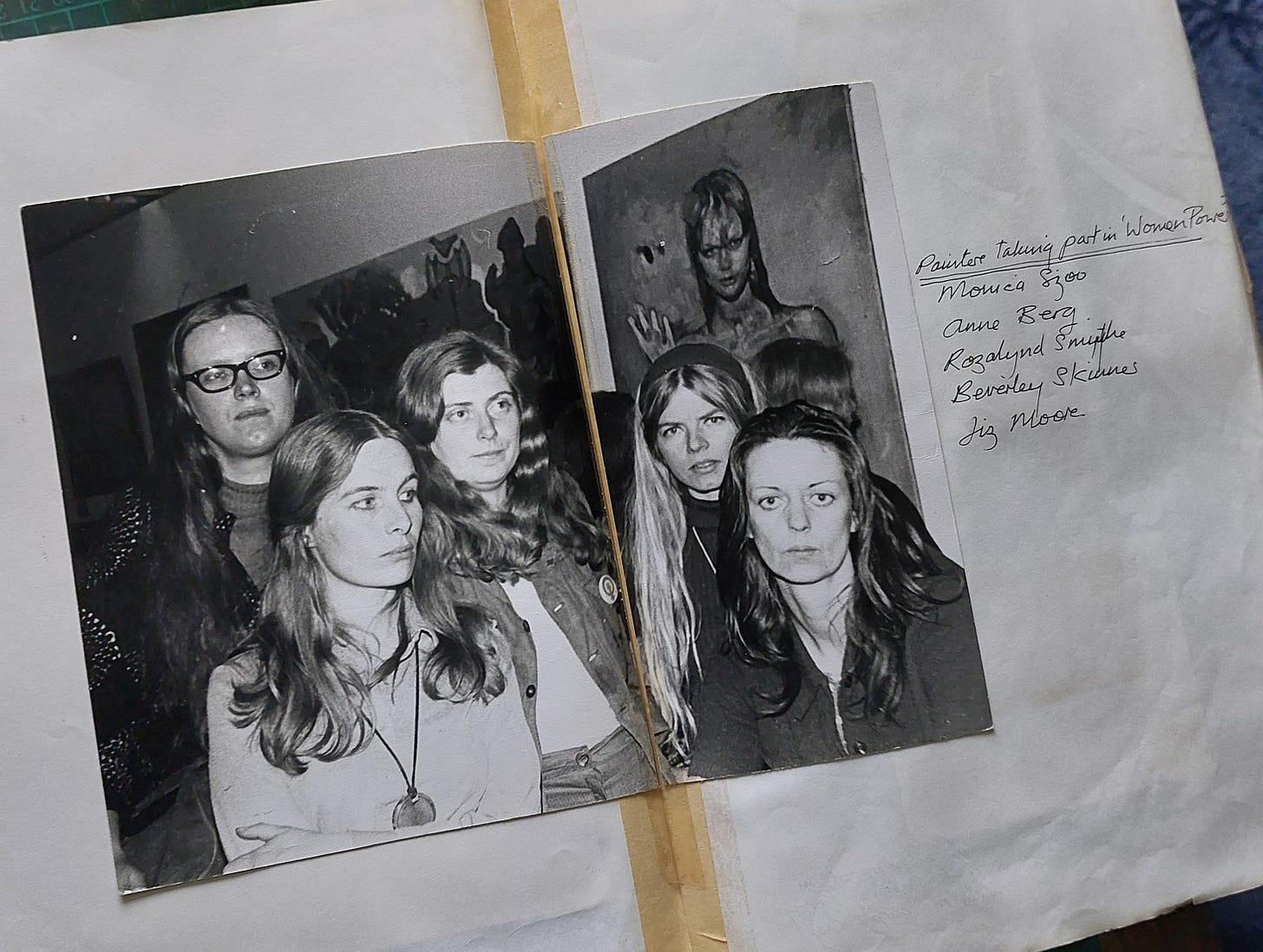

Sjöö and Berg later collaborated again in 1973 on the landmark Woman Power exhibition at Swiss Cottage Library, in which Sjöö’s key painting “God Giving Birth” led to widespread controversy. Sjöö’s paintings are well-known today, and are seeing a resurgence of interest, especially through the brilliant recent retrospective of her work at Modern Art Oxford.

Anne Berg, however, has continued to work under the radar, perhaps because she has dedicated much of her artistic output to deeply personal work that defies exhibition. Since the early 1970s, Berg has kept detailed journals and illustrated them in the style of illuminated manuscripts. Most of them have now been digitised and are available to view on her website.

Comments on the practicalities of life (such as cooking for houseguests) rub up alongside astute observations about her own feelings and those of her friends and family. She documents arguments with her husband and her resentments over being unable to fully commit herself to her art practice due to her responsibilities as a wife and mother. Alongside these personal concerns, she inserts discursive explorations of histories, systems of thought, feminist philosophies, and ideas on painting, as well as decorative borders, sketches, and imaginative imagery.

On one extraordinary spread, an account of getting a lift to a party and going out for a meal jostle against an eruption of painted flames, and a poetic account of “water consciousness” as a feminine state: “Water consciousness was once predominant on earth […]. And now men are so afraid of the flood! They have put their mother in chains, and dreams of love have been purged from the scorched surface of the earth." His arid logic sears her flesh and the cool clear water of living streams never touches our lips.”

This dual ecological and feminist sensibility is a key strand to Berg’s work. In many of her paintings and journal illustrations, female bodies metamorphose into plants and animals. In her 1995 work “Entwined Destinies, Fractured Harmonies” (exhibited for the first time in Cradle), a woman’s powerful body transforms into a tree with roots like snakes. A male figure with both angel wings and diabolic horns hovers behind her, also treelike, while shadowy children huddle underneath her. Ripe orbs float around them, evoking a multiplicitous Paradise Lost, an environmental fruition.

Installation view of Cradle; “Entwined Destinies, Fractured Harmonies” is on the right

Throughout her diaries and paintings, the interweaving of species, words, and looping patterns point to a sense of the interconnectedness of all things, suggesting an ecology of making that still feels highly relevant. Berg writes in her journal, “we are both individual and universal”, a phrase which could be applied to much of her creative output. For instance, “Entwined Destinies, Fractured Harmonies” is both an intimate exploration of her relationship with her grown-up son and his then-girlfriend, and simultaneously a meditation on female power, fertility, and the more-than-human world.

In their manifesto, Berg and Sjöö declare that “womankind, like the surface of this earth, has been ravaged.” This ecofeminist perspective on activism, environment, and gender still rings true; the continuation of interconnected social injustice and environmental injustice since the 1970s is depressing. “DEATH TO THE PLASTIC CULTURE!” say Berg and Sjöö. Yes!

Two of Anne’s paintings are featured in Cradle | Find more of Anne’s diaries on her website

Spotlight on… Hannah Rowan

Hannah Rowan, Prima Materia, 2024. Lost-wax cast iron, hand blown glass with lava collected from Fagradalsfjall Volcano.

Hannah Rowan (b. 1990) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores the slippery complexities of water that draws together a liquid relationship between the human body and geological and ecological systems. She works across sculpture, installation, performance, video and sound to explore the uncertain form of materials. Since becoming pregnant and giving birth, Rowan’s work has begun to embody a further dimension, as the inherent porosity and leakiness of the maternal body becomes a powerful lens through which to consider the fluidity between self and other, individual and environment.

Rowan’s work is informed by situated, embodied and submerged field research, from the Atacama Desert to the High Arctic, to learn from aquatic systems and with the animacy of the more-than-human world. She has participated in residencies across the world, from The Arctic Circle residency in Svalbard, Norway, to the Banff Center, Canada, Taipei Artist Village, Taiwan, and MeMeraki, Cyprus. She has had solo shows at C+N Gallery CANEPANERI, Milan, Galerie Sébastien Bertrand, Geneva, and Queen Specific, Toronto, among others.

Follow @rowanhannah | Website

This newsletter is free for now…

…but in the future I hope to turn on paid subscriptions to make it sustainable for me. In the meantime, I’d love to hear any feedback and whether you might be happy to upgrade to a paid tier in the future!